I wrote a glowing review of the Harvard Extension school after my recent graduation from the Master’s Program after two years of studying finance at the unique institution. It is, without doubt, the best dollar-for-dollar university program available right now that anyone can access. But as I also alluded to in that article, it is far from perfect. While there were of course a few truly terrible classes in my program taught by professors who really shouldn’t be in the jobs they are in, that wasn’t what concerned me. There are some subjects taught in the program that are downright dangerous for an individual to be learning about.

I’m very glad I had a lot of knowledge about the subject of finance before I started the program. By reading dozens of books about finance, studying those who excel in its myriad of disciplines, and managing my own personal and small business finances, I had developed an extensive, real-world knowledge of the subject before starting the Harvard program. Because of this background, I was able to recognize the worst of it and make sure it didn’t cloud my judgement. This article is a collection of all the things taught in my Harvard program that I think should be ignored, and why I think so. Fair warning, there is a bit of financial jargon. My next article will cover a real world example that everyone can understand.

1 – Defining Risk as Volatility

One of the core tenants of financial and investment theory in my Harvard program and most of academic finance is that you define an asset’s risk in terms of its volatility. In other words, if the asset historically has large swings in prices, it should be considered more risky than assets that don’t. It’s this fundamental fallacy that makes financial academics more dangerous than any other single factor.

The overwhelming majority of people have a very long timeline for their investments. While everyone likes to make a quick buck, investing in something like a retirement account isn’t anyone’s attempt at doing so. If you start with the assumption that you are investing for the long-term, why would you define the risk of the assets you are considering as their volatility? It doesn’t matter if the asset occasionally has swings in prices, as long as, in general, it goes up at a satisfactory rate.

Academics have made this error because it was the only easy option for measuring risk. Volatility is an easy-to-measure statistic that can be calculated as a single number and compared to other assets perfectly. Beta is the name of the statistic usually used. But defining risk as it properly should be is almost impossible to do in a statistical fashion. There are two kinds of risk to consider when analyzing potential investments: The risk of a permanent loss of capital, and the risk of generating a subpar return. Neither of these types of risk can be precisely calculated, and usually come down to subjective judgements.

Now this academic definition by itself wouldn’t be truly dangerous if it didn’t tend to find its way into the asset pricing formulas that get used by plenty of investors. Item number 4 discusses that more in-depth. Even on its own though, having the wrong definition of risk can make any attempts to evaluate an asset completely useless.

2 – A Reliance on Forward-Looking Metrics

Economists love to make predictions, and for whatever reason some people in finance like to take them seriously. It’s been proven time and time again that no one can accurately predict the economy, or what individual asset prices will do, or even how an individual company will perform in the near-term. However, academic finance still likes to focus on forward-looking metrics.

My Active Portfolio Management class relied on forward looking P/E metrics exclusively for assigning values to companies and looking at trends. My Financial Statement Analysis class devoted an entire section to forward looking financial statements created from thin air. Finance, by nature, does involve dealing with the future. There is an important distinction that must be made. To be successful, we need to handle uncertainty of the future, not try to predict it, and there is a big difference.

If we know that we can’t predict the future, why does academic finance still act like we can? Academics and financial professionals create forward looking models as their “best guess” of what will happen. A favorite saying by many who do so is “All models are wrong, but some are useful”. True, but as Nassim Nicholas Taleb points out, some are dangerous. Predictions of future metrics have ruined many an individual, scores of hedge funds, and a few times nearly the entire world economy. Even if they’re approximately right some of the time, the damage they do when they’re wrong completely eliminates the gains made.

3 – Anything and Everything to do with Derivatives

Ah derivatives, the darling and devil of the financial world. They have the power to make you fantastically rich and also bankrupt you overnight. Their inherent high levels of leverage make them volatile and powerful assets. And unfortunately, too many people buy them for the wrong reasons.

The Principles of Finance class did a great job of explaining the basis for derivatives. They exist for the sake of providing price guarantees for commodities producers. If a farmer doesn’t want to take the risk that his crops will plummet in value before he is ready to harvest, he simply buys derivatives and offloads that risk to a speculator. This makes sense and is good business practice in some specific instances. And I think there are even some instances where it makes sense to own them as an advanced investor if they remain a very small part of your overall portfolio.

Derivatives weren’t a focus of any of my classes thankfully, and I’m very glad that was the case. However, many of my classmates talked about them very regularly, and their speculative potentials were a core part of many class discussions. I suppose this isn’t surprising in a learning environment full of young, ambitious individuals. They offer the potential for someone with almost no money to make an unlimited profit. However, they also can do the exact opposite in a heartbeat, and it was the excesses of the derivatives markets that turned a housing bubble into a full blown economic meltdown in 2008. And, most importantly, we have to note that derivatives are inherently a zero-sum game. For every dollar you make, someone else has to lose one.

4 – Trying to be Exactly Right about Investments

More than perhaps any other field, finance suffers from a condition known as physics envy. While physics deals with exactitudes and observable and calculable phenomenon, finance is the exact opposite. It lives in a world of constantly changing and completely unpredictable factors. As mentioned above, accurate forecasts are impossible, and true insights are almost always qualitative rather than quantitative.

Physics envy happens when a social science tries to turn itself into a hard science that can be “solved” entirely with math. All social sciences tend to stumble occasionally into the physics envy trap, but finance has delved the furthest. So called Quant funds and specialists are some of the highest earning people out there. Some have outperformed, but most haven’t, and Long Term Capital Management is a great example of what can go wrong when they take things too far.

The best example of how Harvard goes wrong here was my entire Investment Theory and Applications class. This class is well intentioned, and the professor makes bold claims about his past performance and the potentials of his methods. However, his entire method is based around trying to be exactly right using complex mathematical calculations.

For the final project in that class, we had to create a report with a provided template. It involved picking a portfolio of four stocks from a group he gave us, and then running historical performance numbers. While it looks really impressive, it has a fatal flaw. Past results have absolutely nothing to do with the future outlook. Hindsight is 20/20, and it’s easy to just pick the winners when you’re doing it after the fact. The 28 page report I created to his specifications earned an A in the class and looks very impressive and smart. But it certainly doesn’t offer any unique insights, and I would strongly encourage anyone bored enough to read it NOT to build the portfolio it suggests. I’ll admit that I was gagging a bit the entire time I wrote it.

5 – Technical Analysis

Lastly, I have to touch on the area of finance and investment thinking that I think is the most worthless: so called “technical analysis.” While it has a great name that makes it sound advanced and scientific, this method of analyzing asset prices is anything but. It was talked about in several of my classes, including Active Portfolio Management and Investment Theory and Applications.

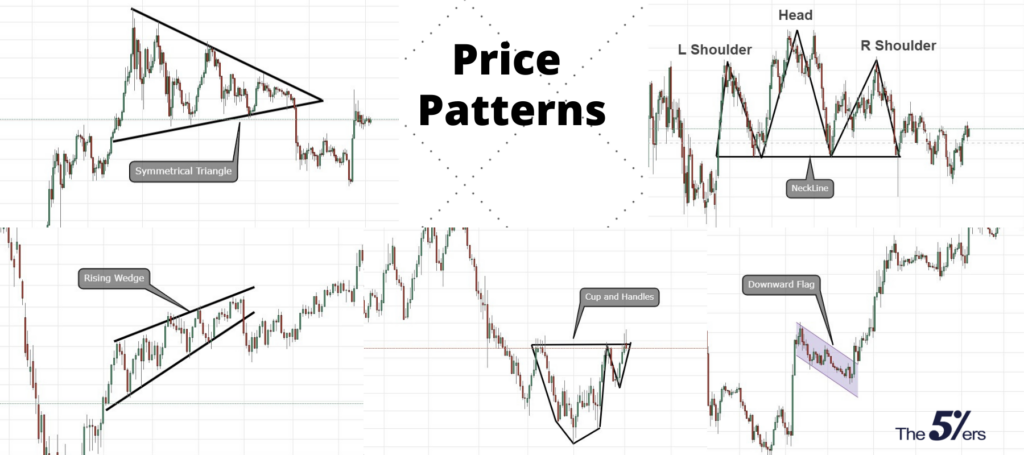

Technical analysis is basically the idea that you can look at the graph of a given asset’s price, spot some kind of trend, and then make an accurate prediction of the price based on that trend. Keep in mind that I didn’t say anything in that description about the fundamental, underlying economics of the asset. Those aren’t considered. Only the movements of the price in the market are examined. Here is a great example of a chart showing many of the trends that are looked for:

It baffles me that anyone thinks there is real insight in anything like this. At least with the previous four points, those who are using those methods are at least considering the value of the underlying asset of a security, even if I think their methods are flawed. But here, analysts are just drawing shapes on a graph and thinking it predicts prices. This is a little like picking stocks based on flipping a coin. You’ll be right some of the time, wrong some of the time, and making an intelligent decision none of the time.

In Conclusion

Finance is a unique field, composed of an infinite number of completely unpredictable variables, yet simultaneously requires you to make guesses on what will happen in the future. Harvard taught me many great things, but also a few that are terrifyingly dangerous. Not all of them are Harvard’s fault. The whole industry is rife with both scams and poor thinking. And physics envy is a very real problem that needs to be acknowledged.

Thankfully my real-world financial education allowed me to spot the most dangerous teachings. In fact, at times it caused me to outright disagree with my professors. While this was never good for my grades, it was VERY good for my net worth. In my next article (and the last of this series), I will be sharing the story of how one of my professors told me my stock pick ideas were stupid, and then how the investments I made in them tripled over the next year and half. Make sure to subscribe to get the full story.